May 23rd, 2022

Jamie Burnes, “Dani the Hare,” wood and steel, 75″ x 24″ x 46″

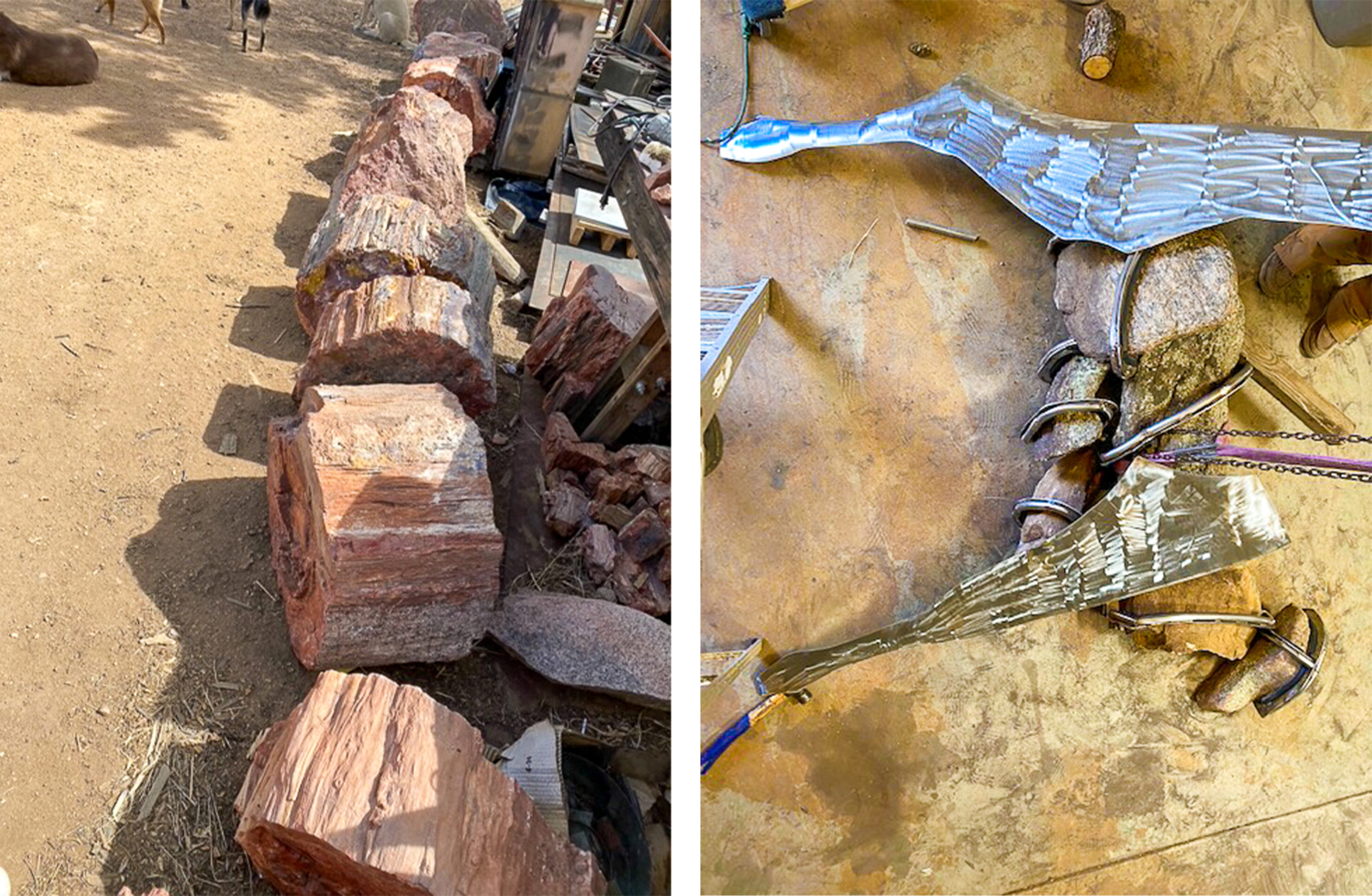

Jamie Burnes answers the phone outside of his Santa Fe, New Mexico studio. As we chat, he sits in his truck, parked in the middle of his junkyard. For sculpture artist Jamie Burnes, his “junkyard” is more like a treasure trove. Strewn throughout the yard is a veritable cornucopia of steel and wood treasures collected throughout his travels across the US, from thousand-pound buoys from World War II to 10,000 pounds of petrified wood. Scraps of steel are piled alongside tree trunks from all corners of the country — everything from locust trees from the Northeast to Cypress trees from California.

Giant Decommissioned WWII buoys formerly used for mooring tankers in the Gulf, now in Jamie Burnes‘ junkyard and pictured alongside his late dog, Stickerburr

These odds and ends he collects in his junkyard serve as an endless source of inspiration and keep him pushing and exploring new and interesting approaches to his work. With an eye for finding diamonds in the rough, he transforms man’s discards into gorgeous works of art.

Slices of various petrified wood tree trunks and interesting steel scraps cover Jamie Burnes‘ junkyard and studio

Burnes first discovered his love of sculpture through a mentor, the classic Italian sculptor Adio diBiccari. The sculptor was renowned for his clay and bronze sculptures from classic busts to architectural gargoyles. When Jamie Burnes was in high school, Burnes got an internship with the artist where he was given the opportunity to recreate many of diBiccari’s most famous works under the tutelage of the artist himself. “I just loved it,” Burnes says, “Right away I said to myself, ‘I want to make sculpture.’ I was really attracted to working with my hands.”

The barn Jamie Burnes grew up in where he first learned to weld

Around the same time as his internship with the artist, Burnes’s family rented out an outbuilding on their property to a man who refurbished vintage race cars. The tenant used to race Saab rally cars and then, on the Burnes’ property, would “buy old Saabs, rip them apart, and weld in race equipment.” It was through assisting this tenant with his race car refurbishment that Jamie Burnes first learned how to weld. “Once I started training in sculpture, I really liked welding the best. There’s something so immediate about it. The welds are so strong that you can get really dynamic and interesting sculptures out of it, because you get such a strong connection on such a small point.”

“It might be through their name or their demeanor, but many of my works remind me of my friends, others of personalities in the arts, or characters in a book. That is how many works get their name. This is my version of my late dog, Stickerburr.” – Jamie Burnes

Through welding steel, Burnes is able to translate his artistic vision more readily, no matter how abstract or challenging achieving such a vision might seem. “With welding, it’s a lot more like working with clay in that you can add and subtract very easily. You can cut something off or well something back on and change your mind. It’s pretty forgiving in that regard.”

Burnes is further fascinated by and appreciative of steel for its simultaneous strength, malleability, and durability With large-scale outdoor sculpture, those qualities are critical aspects of art creation. Burnes needs to know that his works will last the test of time, no matter the environment they’re in. His installations have been placed all across the country, from the hot, vast desert of the Southwest to the snowy mountains of Park City. His sculptures must withstand all climates, and steel makes that possible.

Jamie Burnes, “Gabriel the Horse,” wood and steel, 76″ x 101″ x 22″

As a large-scale sculptor, Jamie Burnes often must think about the logistics of his creation more than most artists in other media. The media he uses in his sculptural work must be thought out logically; however, Jamie Burnes’ interest in steel and wood dives deeper than the purely logical into the more cerebral.

Jamie Burnes is most interested in the ways in which the natural world intersects with the man-made world. That’s part of what first interested him in continuing to use steel and wood as his media. “Steel is ultimately iron that’s extracted from the mountain. So it’s like rock in a way,” Burnes explains, “However, it’s also so manipulated by the hand of man, so it’s like a rock that’s melted and purified and rolled into sheets. I love the idea of then returning it with the natural elements to make a cohesive, yet different work.” By combining a material that’s been manipulated by man like steel with a material that’s created entirely by nature like wood, Burnes explores the connection humans have with nature.

Jamie Burnes‘ abstract and animal sculptures installed outside his studio

He furthers this return to the earth through his treatment of the media. Not only does he prefer to use more earth tones in his finishes of the steel, but he also hammers the steel to give it a more natural, organic look and shape. “Sometimes in my studio when I’m hammering away, I think about how ironic it is to take the steel and make it back into something more natural after it’s been so carefully worked on by so many hands of man to not be natural.” This circle of life that his media undergoes doesn’t bring his materials quite back to their original natural state, but instead breathes beautiful new life into them once more.

Jamie Burnes, “Aeolus’s Tantrum,” CorTen steel Black Locust and White Oak, 132”h x 148”w x 212”d

Burnes’ appreciation of the origins of his media, as well as his interest in its fresh, new purpose gives his work a timeless quality. He remembers one show in particular that spoke directly to this blending of the new and the old, the natural and the manmade: “It’s funny,” he remembers, “I had someone come up to me at a show and say, ‘oh wow, I love your work — it’s so futuristic,’ and then about 20 minutes later someone else came up to me and said, ‘I love your work — it’s so medieval,’ and they were talking bout the same piece.”

Burnes’ subject matter is just as timeless as his artistic style. He creates both works of abstraction, like his “Ring” sculptures, and animal works like his horses, bison, and more. He first explored depicting animals — or rather, something like it — in his work in college, where he created a series of sculptures of micro organisms called Dinoflagellates for his Senior Thesis project. These organisms, not quite plant, not quite animal were well suited subject matter for the Sculptor major with a Microbiology minor.

Left to right: Jamie Burnes’ “Dynoflagellate” sculpture | Jamie Burnes, “Jasper the Feline,” wood and steel, 36″ x 24″ x 21″

From there, Burnes’ work has evolved into a vast oeuvre of animal sculptures. Originally inspired by the tiniest of creatures, Burnes now makes his mark depicting creatures of larger than life scale and grandeur, from towering stallions to foreboding bison.

Burnes’ sculptures are now so vast and incredible in scale that the artist must always be cognizant of the logistics of transportation and delivery during creation. Burnes elaborates: “It’s funny, you kind of make these sculptures thinking about the coolest thing that you can make, but now I’m getting pretty good at the logistics as well.” In fact, Jamie Burnes has an outline of the Gallery MAR entryway sketched on his studio wall just so that he can ensure that his works will fit in our gallery to be seen by you.

A horse sculpture by Jamie Burnes in Gallery MAR

We love to watch the orchestration of these transportations and installations, as nerve-wracking as it might seem, knowing and trusting all the while that our artist has done all preparations to ensure his work’s safe delivery. As much as we love seeing the artist’s work installed in our gallery, the artist loves making work for our gallery and our collectors.

“I love working with Gallery MAR,” Burnes says, “It’s more of a personal, almost family-like experience. Part of Maren’s philosophy is to have her artists be more included in the conversation, and I really love that about it.”

The delivery of “Dennis the Bison” to Gallery MAR

If you’ve ever been lucky enough to swing by the gallery on a day when Jamie Burnes is delivering one of his pieces, you were certainly in for a mind-boggling performance. Making the sculptures proportionate enough to fit through the door is challenging enough, but getting it through the door is another, fascinating, yet challenging ordeal. It takes multiple people, small forklifts, and occasionally — for his larger installations — flatbed trucks to move the artist’s work.

Gallery MAR owner Maren Mullin with her girls in front of a Jamie Burnes horse sculpture in the gallery

Burnes remembers one particular installation of an extraordinarily large piece that took him a full year to create and months to install. The 17’ x 14’ x 13’ sculpture of a nautilus was made up of over 30 locust trees and weighed several tons. The piece was carried on a flatbed down the highway to the seaside where it now lives as a show-stopping homage to the sea.

Although all of Burnes’ works are adept for any landscape, sometimes Burnes will make works with particular landscapes in mind. For this, the artist first does his research. He collects photos from every angle of the landscape, to see how the work will look in its installment from every angle.

Jamie Burnes, “Cow and Calf,” (cow) 43”h x 68”w x 29”d (calf) 34”h x 46”w x 21”d, steel and stone

When possible, Burnes will even take a trip out to where his piece will be installed to get a greater sense of the environment and the landscape where the work will live. On these trips, he will even take natural souvenirs home with him to include in the piece “For instance,” he recalls, “I created this sculpture of two cows. It was to be installed in a place that had these rocks called pudding stones. The stones are essentially made up of tiny pebbles embedded into rock that were unique to the area. So I took a lot of those stones back to my studio to get a better picture of the space that the sculpture was going to live in. Then I rearranged the stones into these two pieces.”

Jamie Burnes, “Aeolus’s Tantrum,” CorTen steel Black Locust and White Oak, 132”h x 148”w x 212”d

Working these natural materials into his work feels to the artist like a natural extension of his artistic vision. By incorporating other natural found media like cypress trees, locust trees, rock shards, pudding stones, petrified wood, and more, the artist continues to find fresh, new ways to explore our connection with nature. In this way, his works blur the line between studio sculpture and Land Art, commenting on the intersection of man and nature with his material, while also showing through his finished works the ways in which the two worlds can live beautifully and harmoniously.

Written by Veronica Vale

Welcoming Lola and Her Luminous Resin Art to Gallery MAR

Welcoming Lola and Her Luminous Resin Art to Gallery MAR Material Matters

Material Matters Savoring the Season: Summer-inspired Works for your Collection

Savoring the Season: Summer-inspired Works for your Collection